Which praise do you think produced better results in American 5th graders?

“You are Smart!“

or

“You worked Hard!“

Carol Dweck, a psychologist at Stanford along with Claudia Mueller conducted a study across 12 New York City schools to discover that what we thought to be the obvious answer, wasn’t so obvious. Dweck’s study showed that a simple sentence, the positioning of an extrinsic reward, had huge impact on the results of the children’s performance. An article in Wired Magazine explained the study:

When Dweck was designing the experiment, she expected the different forms of praise to have a rather modest effect. After all, it was just one sentence. But it soon became clear that the type of compliment given to the fifth graders dramatically affected their choice of tests. When kids were praised for their effort, nearly 90 percent chose the harder set of puzzles. However, when kids were praised for their intelligence, most of them went for the easier test. What explains this difference? According to Dweck, praising kids for intelligence encourages them to “look” smart, which means that they shouldn’t risk making a mistake.

Dweck’s next set of experiments showed how this fear of failure can actually inhibit learning. She gave the same fifth graders yet another test. This test was designed to be extremely difficult — it was originally written for eighth graders — but Dweck wanted to see how the kids would respond to the challenge. The students who were initially praised for their effort worked hard at figuring out the puzzles. Kids praised for their smarts, on the other hand, were easily discouraged. Their inevitable mistakes were seen as a sign of failure: Perhaps they really weren’t so smart. After taking this difficult test, the two groups of students were then given the option of looking either at the exams of kids who did worse or those who did better. Students praised for their intelligence almost always chose to bolster their self-esteem by comparing themselves with students who had performed worse on the test. In contrast, kids praised for their hard work were more interested in the higher-scoring exams. They wanted to understand their mistakes, to learn from their errors, to figure out how to do better.

The final round of tests was the same difficulty level as the initial test. Nevertheless, students who were praised for their effort exhibited significant improvement, raising their average score by 30 percent. Because these kids were willing to challenge themselves, even if it meant failing at first, they ended up performing at a much higher level. This result was even more impressive when compared to students randomly assigned to the smart group, who saw their scores drop by nearly 20 percent. The experience of failure had been so discouraging for the “smart” kids that they actually regressed.

The problem with praising kids for their innate intelligence — the “smart” compliment — is that it misrepresents the psychological reality of education. It encourages kids to avoid the most useful kind of learning activities, which is when we learn from our mistakes. Because unless we experience the unpleasant symptoms of being wrong — that surge of Pe activity a few hundred milliseconds after the error, directing our attention to the very thing we’d like to ignore — the mind will never revise its models. We’ll keep on making the same mistakes, forsaking self-improvement for the sake of self-confidence. Samuel Beckett had the right attitude: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try Again. Fail again. Fail better.”

Source: http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2011/10/why-do-some-people-learn-faster-2/

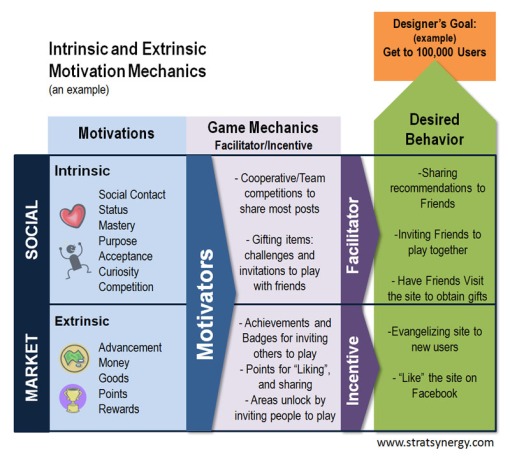

Dweck’s study gives us clues in ways to present awards and achievements which encourage a deeper commitment to the system. If a player perceives to have reached “Mastery” level, does the system encourage or discourage them from achieving more? When designing player comparison charts and leader boards, does the game reward the most effective player motivation? Based on Dweck’s Fixed Mindset vs Growth Mindset illustration by Nigel Holmes, guiding players towards the Growth Mind-set produces a more desirable, engaged and loyal player:

Click Image to see higher resolution chart:

Source: http://www.stanfordalumni.org/news/magazine/2007/marapr/images/features/dweck/dweck_mindset.pdf

Games provide an engaging environment for kids to make mistakes with a low cost of failure, so they can learn and discover a path to mastery. James Gee, a linguist at Arizona State University talks about this, and other merits of educational video games.

“In a world full of complex systems that are interacting with each other to give us more and more disasters – like our current economic system, or our global warming – we really want that video game theory of intelligence. You’re not intelligent because you rushed to be efficient in a goal you never rethought. You are intelligent when you have explored thoroughly and you’ve thought laterally not just linearly, and you have rethought your goals and in modern games done so collaboratively in multiplayer and having to compare and contrast your solutions. And also having different skill sets. In many video games, you play in a team where everybody has a different skillset. Much like modern science where you take big challenges…and you combine scientists with different skill sets but who learn to collaborate and learn to have some common language – that’s actually a way of playing today too.”